Refuge is not a shelter 50 years later A home is not a house

A house as much as a shelter is welcome to fulfill minimum human needs. We are proud, if not we feel lucky to have one over our heads, but yet, are they enough to feel at home, to identify them as refuge from external harm?

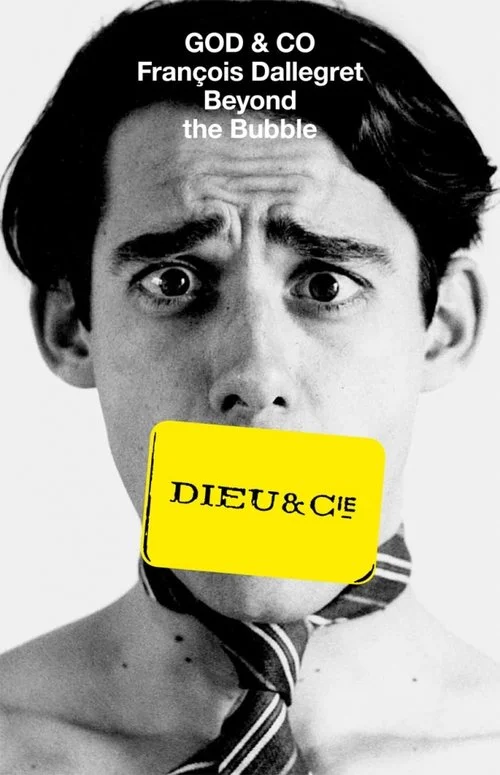

The question about the meaning of home arose in 1965. In those days, it was still a sneaky question floating in a no man’s land between shining hope in technology and shady experience of mankind. Today this alternative tipped into general distrust. Even the planet doesn’t seem to be able to forever host us, therefore, tracking the idea of a home appears more than a bit too ambitious. François Dallegret took note and restricted henceforth his query. Urgency catches up with wondering. So the different titles he envisioned to a today’s counterpart give an account of the new pondering: “Dead end”, “In/out”, “Oui/non”. Finally to the pessimistic first one and to the basic dialectics inferred in the other two, he preferred to emphasize the continuity of his request. Home modestly becomes shelter polarising house and refuge.

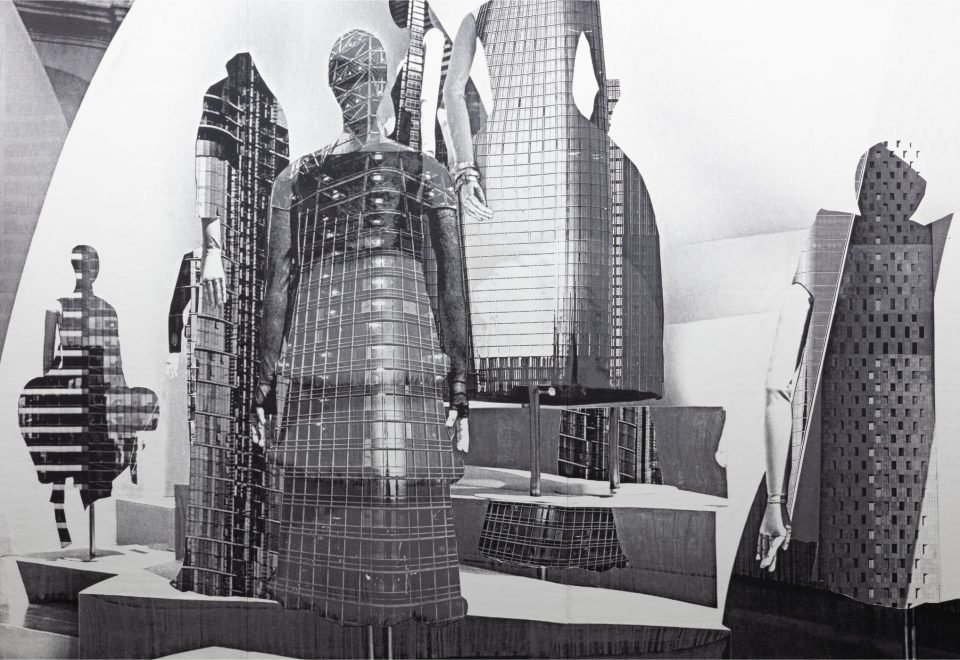

And to grasp the opportunity given by the 2023 Venice Biennale’s main topic, “The laboratory of the future”, the show hold in Spazio Punch at Giudecca appeared to be the perfect place to set the new Environment- structure. Since times went by, the former perfect transparent demi sphere, also known as the Bubble, became a very wild garage, solely signified by the automatic opening of its up-and-over garage door. controlled by a photoelectric cell. Obviously, the installation crosses reference with Tati’s screw ball comedy, Mon oncle, but no need to say his hare-brained ideas long-time reflected on the French born Dallegret.

Indeed, a part from front and back doors in frenzy activity, the realm of calm, peace an beauty of the previous Bubble switched to an urgency room where the resting area is typified by a conveyor belt, stretching and extending,ready to be rooted out in a hurry. As for the former hypothetical home fireplace and the leisure devices, they’ve been replaced by a single neon tube, conspicuously standing in the middle of the room. Admittedly, all these items remain standard industrial objects from a catalog, yet, the refuge installation neither is a shelter nor a “transportable standard-of-living package”. The outside atmosphere, ignored before, summons the living matter into the Nature’s ,fact: through the presence of a powerful ventilator, we shall rather confide that the stampede is approaching.

Perhaps not necessary is either to call out the differences between the American context in the 60’ and the very variegated history of the Giudecca Island. Varying from being an aristocratic refuge to becoming first an industrial site, secondly a rough neighbourhood and returning today to bear a prosperous residential zone reputation, Giudecca plurality imposes its own dialectics. In this context, the irony of the first drawings conveying a message turns into cumulation of illusion distress.

What is a home? What is a shelter? Social Sciences should keep deepen this questions. What about the other way around? What is a house? What is a shelter? The questioning was relevant for the architecture critic Reyner Banham as much as for the young future architect, François Dallegret, wondering if there would be a place for architecture in the technological world. Now a days is doubtless true the house or the shelter constructions subject more to the detriment of the environment and to the political solutions to the immigration conflict than to architectural theory.

“The form follows function” as architectural lynchpin or The modulor as universal rule for the “Unité d’habitation” seem highly overrated.

Though, architects, users, follow Dallegret’s lead : Take it easy or run!

Liliana Albertazzi 2023